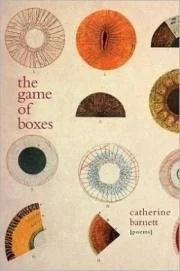

The Game of Boxes by Catherine Barnett

The Game of Boxes

by Catherine Barnett

Graywolf Press

“Can we make a game of it,” asks Catherine Barnett in the opening line of The Game of Boxes, “race across the yard / and collect the trash?” It is a question, on one level, about a mother’s attempt to entertain her child, but it is also a question about fitting the lyric to its subject, about whether the play of poetry can transfigure the traditionally isolated self of the lyric poem. What, Barnett asks in this collection, can the lyric do? What are its limits? And what, in turn, are the limits of the self?

In a generation of poets too often contented with a hermetic mimesis of thought—what one recent anthology called “the representation of temperament/subjectivity/thinking in the moment”—Barnett’s poetry engages those liminal points where the self becomes enmeshed in broader questions of philosophy, history, and aesthetics. In place of a ludic opacity, the poems in The Game of Boxes—often spare, many times understated—represent a sincere poetics committed not to “the moment” but to taking seriously an intellectual tradition too often eschewed by the contemporary postmodern lyric.

At the heart of this collection, Barnett’s second, is an engagement with Kant’s idea of the sublime, namely that the self experiences both terror and dread in the face of the infinite—whether death or, as the Romantics understood it, the implacable force of Nature. Barnett develops this idea not in abstract philosophical language but in a series of images drawn from the world, images that together suggest a finite self negotiating what Coleridge called that holy dread at the edge of infinity. “Tell no one where we go at night,” she says in “Chorus,” one of a sequence of poems spoken in the collective voice of a group of children at once naive about and cynically perceptive of the world around them:

in our sleep, how far we walk,

toward what, but accompany us

to the soundings, the quicksands,

and the rocks.One of the functions of the chorus in Greek drama was to articulate characters’ hidden fears and secrets, and indeed the collective voice of Barnett’s “Chorus” sequence attests to the way that small moments of isolation, like sleep, are shadowed by the specter of something much more ominous and ultimate. “What’s wrong?” ask the children of their mothers in another “Chorus” poem:

To keep from answering, they keep reading.

The Book of Illusions,

The End of Illusion,

and On Not Being Able to Sleep.

But we know more than they think.The mother-figure posited by this collective voice exists in a liminal position, a figure of projected stability who nonetheless borders always on despair and panic. In a later “Chorus” poem, the children ask “So who mothers the mothers,” describing

the lies of mothers scared

to turn on lights in basements

filled with mothers called by mothers in the darkThis is the Kantian sublime, that pervasive dread that at any moment the self will be utterly destabilized in the face of the cosmos. And The Game of Boxes, a book in three sections, develops this idea through a tonal unity hovering always at the edge of catastrophe, a voice perpetually aware of imminent danger, perpetually haunted by loss.

The book’s second section, a gorgeous love sequence titled “Of All Faces,” describes the mother-figure of the first section as, now, a lover whose relationships straddle this same divide between self and universe, love and dread. “Still, your pale blue stare—” Barnett writes, “puts this havoc in the air.” The line is entirely Dickinsonian—its end-rhyme, its use of the dash—and, like that of Dickinson, Barnett’s poetry revels in revealing the pervasive presence of mortality behind even something as putatively immortalizing as love. The lover in these poems

know[s] agape means both dumbly

open and love not the kind of love

that climbed the stairs to you.Yet even knowing this, she remains unsatisfied with the “kind of love” available to her, a limited physical love constantly overshadowed by a purer, inaccessible love:

He lets me want,

touch, cry:

he’s a lozenge of smut,

almost hollow inside.The speaker-lover in The Game of Boxes longs for what Kant calls the “pure category” of love, unsullied by its embodiment in the endless forms of human existence. This shuttling between ideal and actual, and the omnipresent sense of dread that accompanies it, is rendered beautifully in the poem’s most successful poem, “The Right Hemisphere,” an exploration of the way the ideal beauty of the aesthetic—in this case Mozart—is reduced to and registered by the finite and physical inner matter of the brain. The poem is worth quoting at length:

Late at night the mind quiets, or

when listening to Mozart. All the studies

say so, they show maps of the brain

when you’re having chills listening

to something beautiful the way a man’s cry

is beautiful to me I’m ashamed to say.Barnett notes the proximity in the brain of the areas for processing music and sex, describing “a few men / in flagrante, or whatever that is.”

“Present,” I might have said

though for most of those nights I wasn’t,

not really. I wanted to be.

I don’t like to think about the past,

I was afraid to say “here”

though there I was listening.Barnett’s poetry is at its most wounded and wounding when occupying that liminal position between “here” and “there,” situated in the gap between presence and absence, love and dread. The deictics in the last two lines suggest a speaker alienated from both her previous self and the world around her, a self, as she says elsewhere, “left dallying, straddling the extremes.”

In a collection marked by a remarkably effective tonal and thematic unity—nearly every poem explores the ideas discussed above—perhaps the only misstep is Barnett’s hesitance to let the language of the poems itself go to these “extremes.” The speaker here is entirely in control of her language, never given over to the chaotic infinite she describes, an infinite that could have registered itself at the level of form, for example, in greater syntactical discordance or rapid oscillations in tone. In the same way, the book’s thematic unity sometimes falls flat, as Barnett resorts to rhetorical description in place of a more vivid making; when much of the collection meditates on very similar ideas, those ideas threaten to become worn and expected by the end of the book, where one poem, “Vast & Lonesomely,” ends with an unsatisfying description of “a good day for sleeping, / a fascinating day.”

Nonetheless, The Game of Boxes is that rare occurrence in contemporary poetry, a collection at once emotionally devastating and intellectually sharp, turned inward to the working of the self and, more importantly, outward to those points of contact where the self is troubled and destabilized by the dread-inducing universe of which it is a part.