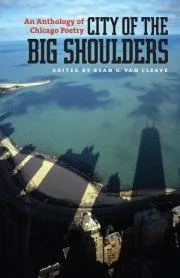

City of the Big Shoulders: An Anthology of Chicago Poetry, edited by Ryan G. Van Cleave

City of the Big Shoulders

Edited by Ryan G. Van Cleave

University of Iowa Press

I grew up in Chicago. For graduate school, I lived in Western New York, Utah, and Alabama. I will always prefer Chicago. We Chicagoans are an unpretentious and modest lot. Perhaps it’s from surviving all those horrible winds. We know that sometimes all you can hold on to is the essentials. Sometimes you’ve got to let everything else get carried by a force of nature.

Ryan G. Van Cleave’s new anthology of Chicago poetry, City of the Big Shoulders, succeeds in displaying the essentials as defined and described by a diverse crowd of Chicagoans. It is appropriately inclusive of people of different cultures and temperaments, though not poetry of all styles. He has privileged straightforward narrative and lyric poems, staying away from anything experimental, yet wholly succeeds in creating a fun and accessible anthology. It could easily be used as a textbook in the high school or college classroom.

I see all anthologies as pedagogical tools. The anthologist essentially says through the organization of his book: “Here are examples of what I found that illustrates this particular theme, aesthetic, or politics. Read it and learn through what I’ve assembled.” Van Cleave introduced me to a lot of poets I was unfamiliar with. My favorite poems include Michael Filimowicz’s “Radar Ghosts.” An excerpt follows:

in the zeppelin’s windows the aquarium city

shows a gold onion dome unspiraling

blossoming for docking atop a new office tower

suspicious and gaudy in 1928

when travelers with visas and faith in their telescopes

sporting new lenses and shiny screws

conspired with mapmakers in the viewing lounge

to designate a continent’s armpit

This poem represents Van Cleave’s main preference: poems that possess a strong discursiveness, a streamlined talkiness. You can see this again in Jarret Keene’s “Chicago Noise (Love Letter to Steve Albini)”:

Steve, there’s something about your band Big Black

in the morning that helps me to more effectively hate birds outside

my window as they chirp ridiculous tunes about nothing to no one . . .

One of the pitfalls of this sort of poems is they can produce an ingratiating slickness. Mostly the poems here avoid that trap.

Van Cleave is a tireless veteran of anthology. There’s no denying he knows what he’s doing. With Virgil Suarez he’s produced several anthologies that include Like Thunder: Poets Respond to Violence in America, American Diaspora: Poetry of Displacement, and Vespers: Contemporary American Poems of Religion and Spirituality. Also, with Chad Prevost, he created Breathe: 101 Contemporary Odes.

Perhaps more important, Van Cleave proves himself to be well read. One of the codes of honor of an anthologist is to include not only the most obvious canonized writers but also the emerging or unpublished. The alphabetical order of the contents often results in new poets appearing side by- side with established poets. Who wouldn’t want to include a poem that opens as “Sandburg Variations” does by the well-known Campbell McGrath? Next to it is a poem by the relative newcomer Marty McConnell. Here is the opening of McGrath’s poem:

Money courses through Chicago’s veins like the essence urging the redbuds into bloom, tulips made wiser by the memory of snow, template of April and the daffodils paper-hung, bereft, the white whale of winter rendered unto fat.

Patricia Smith offers another example of the energy in the anthology:

SOUL Butcher for the Country,

Heart Breaker, Stacker of the Deck,

Player with Northbound Trains, the Nation’s Black Beacon;

Frigid, windy, sprawling,

City of Cold Shoulders.

More flat and direct is the opening from John Bradley’s “I Saw You”:

Where: Wilton Ave. The algebra of your nameless blond hair. I think you went offline, which made you flutter, then disappear.

Where: Weiner’s Circle. You favor green or red South American scarves. I wear useless knowledge. Save my village.

Many poets tend to use anaphora in a perfunctory way. Bradley uses it to highlight a diversity of sounds and images.

One thing missing from this vibrant collection is a diversity of form—particularly the way the poem looks on the page. For a tribute to a city known for its architecture—designed by Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and others—you would think Van Cleave would want to represent poems that take up space in different ways. Most of the poems are aligned predictably on the left-hand side of the page, either in a huge column or in couplets or quatrains. Perhaps this is why Mary Cross’s “summer news” (written to Joseph Cornell, we’re told) seems to draw attention to itself. It’s aligned on the right, has a lot of fun with spacing between words and phrases, and delights in offbeat choices of capitalization as well as punctuation. These lines appear at the end of the poem:

they’ve hired a crew of border collies to bark

at anything that flies

as they glide along the shoreline in rowboats manned by lifeguards

some say their collars are radioactive isotopes flattening the atmosphere

for sale at a kiosk on the pier

All in all, Van Cleave has done a terrific job here. I bet that John Dewey, one of Chicago’s most important philosophers, who advanced the idea of pragmatism, would be proud. Van Cleave never falls into the trap of tokenism in his inclusion of marginalized people. He has created an accessible anthology that rarely settles for anything less than useful, companionable poems that serve to define the Third City in the early twenty-first century.