Steve Almond on Finding the “Holy Jolt” in Your Writing

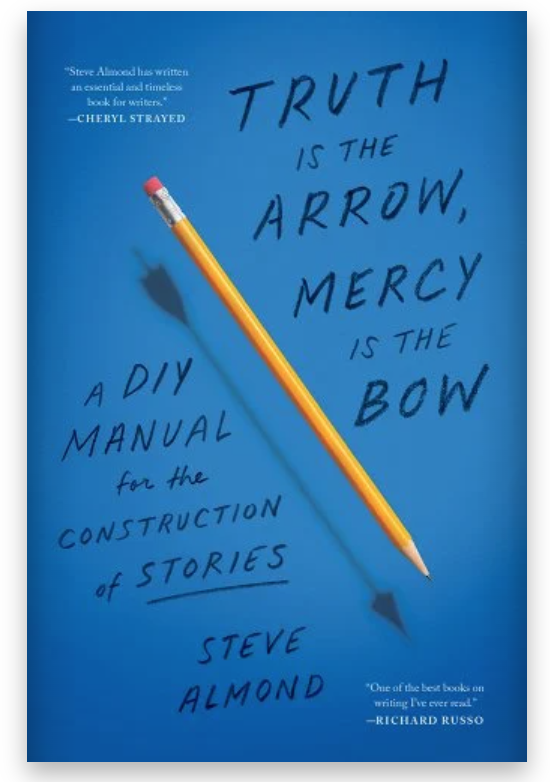

In a recent flight, I booted up my laptop as we passed through 10,000 feet to outline these interview questions for Steve Almond. After thirty years of teaching and eleven published books, Almond has lassoed his “struggles as a writer” and his thinking about writing into one knock-out book on craft. But before I could delve into Steve Almond’s Truth is the Arrow, Mercy is the Bow: A DIY Manual for the Construction of Stories, a feature film on my seatmate’s screen caught my eye. It turned out, Almond was flying with me. Or at least, his first feature film based on his eponymous novel, Which Brings Me to You (co-written with Julianna Baggot) was being featured on the airline’s choices of “New Releases.” How could I possibly choose—finish the interview, or watch his novel play out during the long flight? I choose the latter. Given Steve Almond’s illustrative, collaborative career, there is an endless array of choices for the reader/viewer. From podcasting with Cheryl Strayed on “Dear Sugar” to landing on the NYT Bestseller list for several of his books, Steve’s career has been, what we call, in aviation, “ceiling unlimited.” I’m so grateful he took time during his busy debut craft book launch to answer questions for TriQuarterly readers.

Laura Joyce-Hubbard: What sparked the idea for this project and what has this process been like for you––writing and publishing your first craft book?

Steve Almond: Full confession: “Truth Is the Arrow” is not my first book about craft. Back in 2010, I decided to write a book called “This Won’t Take But a Minute, Honey”. As I conceived it, the book would have two covers and be readable in two directions: one side would be 30 micro essays about writing, and the other side would be 30 short stories. I was hoping that Random House, my publisher at the time, would be wildly enthusiastic about this weird little book. They were not. But I really wanted to put it in the world, so I got in touch with a friend of mine, the graphic artist Brian Stauffer, and sent him the text. He sent me back a bunch of incredible cover images. This was right around the time that desktop publishing was kicking into high gear, so I got in touch with the good folks at Harvard Bookstore and sent them a PDF of the covers and text and they used their Expresso Book Machine to make the book. It took about five minutes and the result was just gorgeous, this little, pocket sized book. So I started selling copies of this book whenever I taught, because the essays were really just a compendium of the things I was telling my students over and over. I never got an ISBN or put the book on Amazon, because I saw no reason to do so. I was quite happy selling the books out of my backpack, for cash. It just cut out all the middle men, direct from artist to audience. In fact, I enjoyed that experience so much that I made two other DIY books (“Letters from People Who Hate Me,” and “Bad Poetry.”)

All of which is a long-winded way of saying that “Truth…” is really my second book about writing. In fact, I was able to smuggle the best bits from “Minute, Honey” into the new book, in the form of the Frequently Asked Questions at the end.

As much as I loved putting “Minute, Honey,” into the world, I knew that I had a lot more to say, as a writer and teacher, so I started gathering up some of the craft talks, and keynotes, I’d delivered over the years. Often, people would ask me to send along copies of these talks, and I was like, “Sure! Just email me.” I’m not sure when the idea took root to pull those talks together into a book, but I’m sure it had something to do with finally figuring out how to write a novel that didn’t totally suck, which gave me the feeling that I’d learned enough, through my own failures, to help other writers.

LJH: I love the way you’ve organized the book into three sections: “There’s a section on craft, a section on the origins of story, a section that reckons with the psychic and emotional barrier we face in our ambivalent pursuit of truth.” How did you land at this three-part structure? And what do you hope the reader will take away?

SA: Yeah, so craft is important. It’s really helpful to step back from our work and consider what we’re doing with character, plot, narration, etc. But craft only gets you so far. In my own experience, there are two other parts to the writing life: inspiration, and inhibition. Where stories come from, and the internal forces that hold us back at the keyboard. I really wanted to deal with the whole creative process. How we get fired up, and how we can sometimes, without even knowing why, lose that fire. So I wrote pieces about obsession and desire and sex scenes that were modeled on my generative classes, with prompts to get folks writing in a loose way. And I also wanted to write about my own struggles with what I call The Evil Voices: ego need, distraction, competitive envy, fear of failure, writer’s block, anxiety about exposure. It felt sort of disingenuous, or irresponsible, not to mention these struggles, because they’ve been such a big part of my writing life. Sigh.

LJH: Can you talk about your relationship to the novel and how it informed your book of craft?

SA: For years, I identified myself–privately, if not publicly, as a failed novelist. I was just terribly invested in trying to write a novel. And I wrote novel after novel, and each of them, for whatever virtues they initially offered, fizzled out. As I write in the book, I often fell into a trough after failing at these novels. And I would kind of pick myself up and write some non-fiction book, usually about one of my obsessions (candy, football, the 2016 election). Then, maybe eight years ago, I just gave up on the idea that I would ever write a novel. I let it go. And somehow that act of surrender–which felt so counter-intuitive at the time–opened up this imaginative space within me, and the muse was kind enough to walk Lorena Saenz, the heroine of “All the Secrets of the World” into that space. Because I’d failed so often at the novel form, I’d actually collected a lot of data about the nature of those failures, so, with Lorena’s help, I was able to keep writing without getting too much into my head.

This is why I’m such a big fan of failure: because you learn a lot more from your failures than your successes.

LJH: I love your touching dedication: “For Richard Almond / Blunt dad, soul doctor, truth seeker.” Can you share any insights on the role of “truth [as] the arrow” as it relates to your influences?

SA: You don’t get to choose who your parents are, or what story you’re born into, but I was pretty effing lucky. Not that my parents are perfect. But they’ve always been present in my life, and been good models of what a meaningful life is. I wanted to acknowledge that, both in the dedication and in the book itself. But the other influences that I cite are writers such as Megha Majumdar and Natasha Tretheway and Jane Austen and Lorrie Moore and Meg Wolitzer and my Virgo queen Cheryl Strayed–all of whom wrote books that blew me away, and that helped me provide some concrete examples of writers who are making brilliant craft decisions.

I’m a big believer in being as concrete as possible with students. It’s not enough to hold forth, to make these big, abstract statements about (for instance) how to manage chronology. It’s much more useful to provide passages that model how to do it right. Those influences don’t just inspire you. If you study the decisions they’re making, they become your teachers.

LJH: You recently taught an incredibly popular craft class based on Truth is the Arrow, Mercy is the Bow for Off Campus Writers Workshop called “How to Craft an Irresistible Narrator.” Your class generated a lot of buzz. Here a few questions generated from your wonderful session from writers who attended:

I’d like advice on where you generally utilize your slide into omniscience in your novels, and what triggers you to know the story needs it. I’ve shifted from calling it the “Steve Almond opening formula” (from two years ago) to “modern omniscience” after your recent session. (Susan Levi)

SA: The move into omniscience is really case dependent. That is: I have no idea when that should happen in your novel, Susan. But I will say that I’m a big believer in establishing that strong, independent narrative stance early in your book. Why? So that you (and the reader) know that it’s available. When I don’t allow for that kind of omniscience, I’ve often gotten trapped in a close third-person POV that limits my storytelling choices.

LJH: In All the Secrets of the World, you use a close third POV and seamlessly go from the thoughts of one character to another and then another—multiple times within a fast-moving chapter. Yet it never feels like head-hopping. What advice do you have for writers on how to best use close third POV and avoid head-hopping? (Nilda Mesa)

SA: Thank you for that kind observation, Nilda. The key to pulling this off, for me, was to establish the narrative perspective of each of the characters earlier on. If we know how Lorena sees the world, and we know how (for instance) Rosemary Stallworth sees the world, then it’s possible to switch POVs without confusing the reader. But the truth is I very rarely switched POV in the midst of a scene in Secrets. I wrote the book in short, discrete sections (usually a single scene), with white space. This structure allowed me to move from one POV to the next without confusing the reader.

LJH: You mention using your writing struggles to inform your craft book––specifically in the area of plot. Can you talk about how this specific challenge has informed your understanding of how to approach, teach, and write plot?

SA: Yeah, I think that being REALLY BAD at something for a loooooong time allows you to start at a very basic level. And that’s what I tried to do with plot. I’m just such a disorganized person, and so bad at plotting stories, that I have to think really hard about how it all works, and kind of explain it to myself. Which is what that essay tries to do: to really break down what we mean by plot, that it’s about pushing your characters into danger, writing scenes that escalate tension and instigate further action, cleaving a chain of associations to a chain of consequences.

LJH: The new feature film based on your novel, Which Brings Me to You (co-written with Julianna Baggot), is yet another feather in the cap of your career. Can you talk about the co-writing process?

SA: Basically, Julianna told me she’d conceived of this novel that would be letters back and forth between two romantic flameouts, who confess to their failed relationships in an effort to figure out if they might make a go of it. I was like, “Uh, ok. Send me something.” And she sent me this great opening scene, where they meet at a wedding. In her version, they had sex in the cloakroom, but I felt like that was too quick, so I rewrote the scene so that they stop and instead pledge to write each other letters. Then I wrote the first letter, from the POV of my character, John. And Julianna wrote me back, in the guise of her character, Jane. And we just went back and forth for a few months. It was thrilling. And just like in any relationship, we eventually started fighting (Julianna and me, that is). This was upsetting, but it ultimately made the book more interesting, because our characters started to fight, and challenge each other, and that’s how real love happens–in those places where you have to look at your own shit and learn and grow.

LJH: I love the scene you described when visiting China to teach creative writing. I found that entire section to be a lesson on craft, scene, and suspense! I particularly loved the way you described one of the students’ work, when she read it aloud to the class: “We’d all felt the same holy jolt.” Can you describe that feeling for TriQuarterly readers who haven’t (yet!) had the pleasure of reading that section of Truth is the Arrow, Mercy is the Bow?

SA: The feeling was that of an entire room full of people (maybe 300 of us), mostly adult teachers, being held in this single simple story, told by this seventh grade girl. It was just such a powerful example of how story can cut through all the noise in our heads and just grab hold of our hearts. That’s the holy jolt.

LJH: Would you like to share with readers what you are working on now?

SA: At the moment, I’m mostly reading student work, because I’m in the thick of my teaching season. Fortunately, my students at Wesleyan, and at the Nieman Foundation, are brilliant, so it’s incredibly exciting to read their work. It’s like a bunch of handmade gifts I get to unwrap each week!

LJH: What advice would you give other writers working on their first novel?

SA: Outlast your doubt. That’s the main thing. Also, remember that the first draft is for you, and you should just let it rip. Down the road, if need be, you can cut stuff that doesn’t work, or rework the elements that don’t feel right. Try to enjoy the process, because it’s the one thing you get to control. And don’t beat yourself up if you wander down a few blind alleys. What we call failure is really just an opportunity to learn.

LJH: Lastly, is there a question you wish someone would ask you about your craft debut? Or one you’ve never been asked about your work in general, but would like to answer?

SA: The main thing I wanted to do with this book was just be in conversation with other writers who are in the struggle. So if there are any teachers who want to assign “Truth Is the Arrow” to their classes, or any writing groups who decide to read the book, as a group, I’d be happy to Zoom into your class/group, if we can arrange a time. Just email me through my website, www.stevealmondjoy.org.

Steve Almond’s Truth is the Arrow, Mercy is the Bow is available wherever you buy books. Indiebound here. Amazon here.