Some Kind of Magic: Excerpts from Her Read: A Graphic Poem and an Interview with Jennifer Sperry Steinorth

Erasure poetry can be startling. Opening the cover to a book—or the pdf of a submission—can take a reader’s breath away when the expected source material is transformed into something new that pushes the boundaries of both art and poetry. A work of erasure is both an artifact and something alive; it is a confluence of static image and text as well as a dialogue between layers of voices that implicitly seem to welcome more voices into its chorus.

Wrought from an old, patriarchal text of art history and criticism, Jennifer Sperry Steinorth’s Her Read: A Graphic Poem shines intertextual light on the presence and work of women in art. Steinorth uses erasure to excavate her own words from the original text as well as to create something wholly new, something both hidden beneath the surface and innovative in a sense of contemporary necessity. Part visual art, part verse, Steinorth’s book is not only a reframing, but also a reclamation. In addition to the excerpt TriQuarterly has published here, Steinorth graciously spent some time answering my questions.

TQ: Thank you for speaking with me about Her Read: A Graphic Poem and the excerpt that TriQuarterly is fortunate to publish here. Let’s start with the foundation for your book: Herbert Read’s The Meaning of Art. In a poetic introductory section titled “Her Apologia,” you shine some light on the origin of Her Read—finding The Meaning of Art at a library book sale, the broader national picture at the time, and the liminal moment before you began to mark its pages with your chosen tools. I’m curious, though, how you arrived at that moment. Did your idea for Her Read exist before you encountered the book at the library sale, or did it evolve while you were reading the book or afterwards as a response to what you had found in it?

JSS: Well, first—thank you so much for spending time with this book. I’m delighted that TriQuarterly has given space to it.

As to the idea of Her Read—I can’t say I had a notion of it before I encountered the source text. I had an interest in erasure and after playing around with the form and reading some book-length erasures, I wanted to try my hand at an extended project. Many of the library discards were charming, hardbound, midcentury texts—made to order. At a dollar a piece, I bought a few. But Read’s book stood out because of its grandiose title. When I saw it, I thought, what kind of balls does it take to write a book and unironically title it The Meaning of Art. Please forgive the sexist pejorative; it was the summer before the 2016 election and the sexism playing out on the national stage was resonant with harmful behavior of men in my personal and professional life. And, of course, our culture loves to talk about balls. At a dinner celebrating a guest writer, one man, a local writer, had recently declared: writing a good poem takes balls. The visiting writer had ovaries.

So when I saw the title, I flashed with rage and thought—okay—my visceral response to this text has to account for something. Maybe I can leverage this tension. I didn’t even realize there were no women artists in the book until I was 30 or 40 pages into the erasure. But when I did, it was no surprise. I understood the prevailing notion that it also takes balls to be a painter.

I should confess that I did not read Read’s text until after I had my way with it. I did this intentionally, because I wanted to see the words as raw material, independent of the contextual meanings Read assigned to them. So, though my book evolved through engagement with the material composition of the book and its general conceit, it was not a response to particular theories. Rather, the book was a response to my experience as a woman and a female artist in the world and the experiences of others I had witnessed. Basically, like a painter, I was using Read for his body. But as I write in the apologia, I did come to admire Read.

TQ: The apologia is a fascinating artifact in the book—acting not really as an apology or defense as it traditionally suggests (since, what’s there to apologize for in the act of creation and art?) but more like an artist’s statement. Without the apologia, the art and poetry of Her Read may have felt more enigmatic; however, it provides some interesting context in a manner that’s both poetic and somewhat exegetical. How did it come to be called an apologia and how do you feel it functions in the book?

JSS: Wow, thank you for this question. The apologia was terribly difficult to write—you take me right back to that thicket! I considered calling it artist statement or preface. Read had a preface. But to duplicate that word felt clumsy. And the work was bigger than that. Apologia seemed right to me, both in meaning and tone. I mean it in the classical sense, not an apology but a defense, a pre-emptive defense against accusations not yet waged but possibly warranted. Perhaps, making art should never require defense; and yet I took the intellectual work of another and dismantled it. I was recalling Solmaz Sharif’s wonderful essay, “The Near Transitive Properties of the Political and Poetical: Erasure” and thought, okay, I am perpetuating a kind of violence. What have I to say about that?

And then there is the question often asked these days: who are you, author, to make this work? What gives you the right? If, as you say, there’s nothing to defend in making art, then perhaps we should not ask such questions, but we do. And for good reason. It felt important to acknowledge that I come to the work from a place of privilege, to articulate some vulnerabilities married to that privilege and other vulnerabilities that inform the text.

There is also a subverted defense of scope. The violence this book explores is not as earth shattering to an individual as other kinds of violence, but it is pervasive, inseparable from our culture and the seed bed for other violences. I wanted to articulate what the book interrogates, and acknowledge what it does not.

So, I guess I’ll push back and say I do think my apologia is just that, a defense—against internal demons of validity and worth and those, for better or worse, that artists face today. And I think the last section, is almost an apology. I anticipate the work falling apart in my reader’s hands. I refer to it as a fumbling—which rhymes with failing. I confess we are filled with faults.

TQ: You’re a poet, educator, interdisciplinary artist, and licensed builder. I’m very curious about those last two descriptors—artist and builder—and how they’ve influenced your writing. In your first book, A Wake with Nine Shades, you experimented with the way the words appear on the page (I’m thinking of poems like “GODDOG DOGGOD GODDOG DOGGOD GODDOG” and the “wink” interludes), but not to the level we see in Her Read. It’s apparent that Her Read is a confluence of your talents and experiences as an artist-builder-poet. Can you talk about your artistic and poetic development in light of your two books and whether you see Her Read as a culmination of your abilities or a stop along pathway of further literary artistic experimentation?

JSS: I think it’s interesting to consider how the things we make, make us: the architecture of our bodies, neurological pathways—determined not only by our genetic makeup and what happens to us, but by the muscles we develop, the processes we attend. I definitely think of writing in terms of theatre, design, and construction.

Dance was my first artistic devotion and formative in myriad ways. When I began to write, I found music was a driving force; a bit later came structure. But I was also concerned with the line as perceived by the eye—its movement across the stage of the page—the fall or flight off the end—and the weight (and grace) of its landing. And though it may be true that, in poetry, line is king, I have long been concerned with unoccupied spaces and felt those fields as active agents. There is crossover here with what visual artists refer to as “negative space.” Of course, unoccupied space is more active in some poems than in others—but it is quite active in my first book, as well as Her Read. I like the way spatial organization can externalize interior shifts—in tone, time, place—or the way space may be used in lieu of punctuation. All this allows more to be said with less. To me this is the essence of gesture. Unoccupied space also creates room for the reader to move inside the poem.

I wager this concern with bodies moving in space derives in part from years spent as a dancer (expressing sans words) and as an architect.

I will say, both Her Read and my first book A Wake with Nine Shades required the fullness of my skills and boundless grace to draft. But Her Read especially taught me how to write it. Remodeling is so much messier than new construction! I did not set out to make a visual poem—I would not have been so bold! I set out to draft an erasure. Visual elements evolved as I interacted with the materials and attempted to solve aesthetic problems. The solutions I discovered were surely impacted by my work in other disciplines, but I also spent two months at Vermont Studio Center (January 2017 and October 2018). Exposure to and encouragement from visual artists there was critical.

As to the future—I definitely wish to keep experimenting! I have a few projects on the backburner; one I think will involve visual elements. I’m also working on a series of lyric essays—which feels like radical experimentation to me!

TQ: You mention that the “remodeling” of Her Read was a messier way to write than starting with a blank page, which is an interesting thought. I’m fascinated by the process by which Her Read was created. I think the book can be considered a form of erasure, in that you’ve obscured or changed parts of the original text to create new text and meaning. But with your use of correction fluid, ink, cloth, and various types of thread, you’ve built up the pages, using an additive process to create the book. Can you talk about how you came to this artistic process and how you see your book fitting within the form of erasure/blackout poetry? How did using only three copies of the book affect your work as you created earlier drafts of the book? Was that limiting or did it help you focus?

JSS: Ahhh, YES! There are lots of additive elements in this book. But when you think about it, even state-instituted redaction with a Sharpie is additive! Marks that obliterate point back to the obliterator.

Initially, I followed rules I’d noted in other erasures. I used words as they appeared in the source text in the order I found them; my only utensil was white corrective fluid. But I couldn’t help noticing the textural effect of my brush strokes, the way technique and the viscosity of fluid could radically alter those effects. As my awareness of these effects grew, so did my intention.

In metered verse, poets often break rhythm for emphasis. Likewise, there were times when I saw a linguistic possibility that could not be achieved without breaking a rule I had been following; when the effects warranted the emphasis, I broke the rules. And as the book progressed, I allowed some of the rules to fall away. I liken this to poets who write contemporary sonnets without meter, rhyme scheme or syllable count.

One particularly challenging constraint was heavily Latinate, abstract language. There were few concrete nouns to ground the poem. Thus, I looked for words inside of words—the pig in pigment, the king in thinking, the imps in impressionists and imperatives. Soon I was making perfect into erect and the art into heart.

So, though I began with a strict set of rules, I took numerous liberties as the book progressed, both in the methods used to make linguistic sense and additive techniques I employed. The progression felt appropriate to an increasing agency I felt in the voices of womxn scratching their way out of the scholarly tome. As evidenced by the illustrations, the source text progresses chronologically; so my speakers’ agency mirrored the increasing opportunities afforded womxn in the modern age. Of course, the progression also chronicles my artistic growth as I discovered and developed new techniques.

Sometimes, after I’d reached the point where a rule no longer applied, I’d double back to earlier pages when the rule was still in effect and break that rule. Often, I could use the move to solve a problem I had not yet solved, but it also worked to foreshadow the rule’s collapse in pages to come. This added cohesion so shifts in rules were less jarring. It occurs to me now, this also emulates the way society evolves; first a few people break a rule (often to dramatic effect) and eventually the rule gets tossed.

Nearly all the additive moves were first employed to solve aesthetic problems. I altered the illustrations to avoid copyright issues. I sewed together pages I no longer wanted seen, or for concision—cutting windows that allowed words and images from several pages to be viewed in a single plate. As I approached the end of the text, and wanted more control, I employed collage.

But you also asked about the three copies of the source text that I used...I should clarify that I didn’t use 3 copies to make one book. Rather, I made the whole book three times on three different copies of the source text. And I made each copy, including the first, thinking it was the last. So, I never had the luxury of saying, oh, that’s not quite right—but I’ll fix it in the next draft. So, if I messed something up, I had to find a fix. I guess this was restricting, but it also necessitated some ingenuity! There was a kind of freedom to this finality. I mean, the pressure not to muck it up was real—especially as I neared the end (and the book was under contract), but I also accepted the impossibility of perfection. In fact, that grace felt essential—central to the conceit. To embrace our wonky bits—to celebrate the work of unmastered spaces.

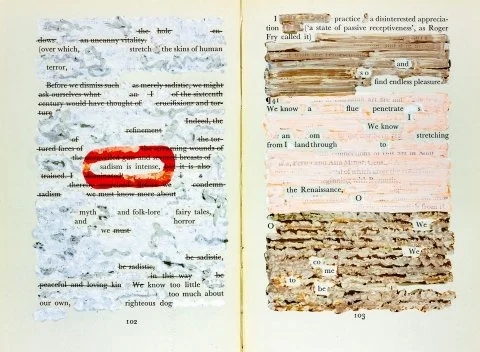

TQ: Let’s talk about the selection you sent to TriQuarterly and is being published here. On the first page/image, a bright orangish-red circle highlights the words “sadism is intense.” Other words on the page are either completely obscured, crossed out, or left unaltered, but they all fall to the background due to the boldness of the circle and the words within it. Although your book is very colorful, there are a few prominent colors—rusty reds, chalky blues, faded pinks, and mustardy yellows. Bright, bold colors are very few and far between—greens and violets are almost, but not quite, nonexistent. Can you elaborate on your use of color in this specific instance and throughout the book?

JSS: Oh, boy. When I arrived at that page, the first thing I saw, smack dab in the middle was: sadism is intense. I thought, Bam! Page done. Then I looked more closely and found so much vivid language—which, as I mentioned, was unusual. I couldn’t let all those great words go unused. So, I came up with two levels from which to read the text: 1) read all the words that are neither obscured nor struck through, and 2) read all the text that is legible, including the words that are crossed out. But both of those seemed to diminish the hilarious understatement of the three words in the center. I still wanted that sentence to rule the page—so I circled it in red.

Red and hot pink were the first colors to enter the text. It seemed natural to me both as a color associated with women and as the original color of the fabric binding of the source text. I was particularly interested in red as the color of blood, of menstruation, that ancient and continuous marker of purity or impurity—depending which misogynist creed one follows. I had also disliked pink for a long time, and I was interested in my aversion to a color used to define females—particularly young girls.

Beyond a few splashes of red and fuchsia, there was not much color in the first artifact. The palette included the color of the page, black ink, bright-white correction fluid, and parchment-colored correction fluid. The parchment color (“buff”) was a marvelous find that allowed me to make patterns, horizon lines, etc. But between drafting the first artifact and the second, that color was discontinued. I was alarmed! My compositions were based on two shades of correction fluid. Eventually, I discovered alcohol-based markers could tint-dry Wite Out. The yellow you see is as close as I could get to the original “buff”—it’s not quite right. On the other hand, I suddenly had many colors to choose from.

I didn’t want to stray far from the light, neutral tone of parchment; I gravitated toward similarly earthy shades (accepting the reds and pinks). But I noticed many of the shades resembled human flesh tones, which made me want to add some darker browns to the color palette. The majority of the figures in the illustrations are white, not to mention the artists, and I wanted to gesture toward the absence of black and brown bodies.

I also added the grays as a watery relief to the earth tones. They maintained balance in a neutral palette that allowed the reds—when present—to dominate.

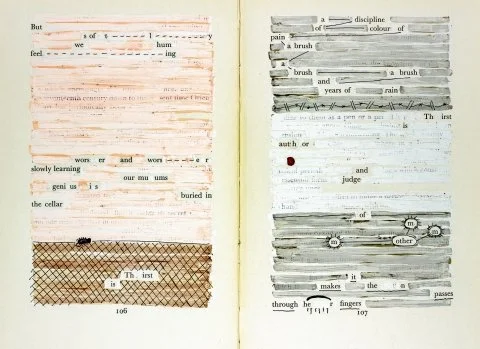

TQ: There are moments of repetition where, by obscuring lines and words, you created a stuttering effect, almost as if the voice on the page was still searching for the right words. These moments also seem like chants, so that the whole book becomes a song-like epic. This second sense is perhaps influenced by the classical art in Read’s book and the fact that your book’s full title [Her Read: A Graphic Poem] indicates that it is a singular, long, graphic poem. As an example of repetition in your book, the readers can see page 104 in the TriQuarterly-published except with the repeated word “mother.” Also, on page 107, “a brush” is repeated. What was your intent when you used the words or letters on each page to make these types of repetitions?

JSS: Thank you so much for these generous observations. In truth, I’ve always been a sucker for repetition. I love the music and the way a word’s meaning can multiply and divide—a rose is not a rose is not again the same rose! But particularly in Her Read—as I worked within the constraints of an already written text, semantic repetition helped to maintain syntactic continuity. That is, repeating words and phrases sometimes allowed me to pivot midsentence without dropping the thread entirely. It also made use of what was in abundance. The lack of concrete nouns made image building a challenge, but I tried to make up for this with music, tone, play with diction, rhetorical gestures. Repetition could be leveraged to aid all of these poetic devices.

And I have to say, I’m humbled and honored by your calling this “a song-like epic.” The notion of “chanting” (and all its wonderful liturgical connotations) hadn’t explicitly occurred to me, but is a perfect articulation, in my mind. I was cognizant of the way repetitions in the book emulate the prolific objectification and subsequent erasure of womxn across time, the way such repetitions shape our culture, our collective (if unwritten) story. We are told the sins of the father are visited on the son—but as mother begets mother, and other begets other, cultural prisons are also inherited. And to leverage the incantatory power of repetition, of “chanting,” lends itself well to a book that interrogates Christianity’s indoctrination of misogyny (and that of other Abrahamic faiths).

I love the oration of the particular section you mention; in the repetition of mother and mama, I hear a child’s murmur. When we say an issue is political, we can hold it at a distance. But the issues here have not only been with us since the beginning of time (as we know it) but since the beginning of each human born of flesh in blood. Our understanding of self, of other, of gender are printed on us so early, so intimately. One line you mention is among my favorites in the book: Thirst is/ a discipline/ of colour of/ pain/ a brush/ a brush a brush/ and/ years of rain. The repetition of the word brush physically and sonically intimates the recursive motion of brush strokes—which might be the brushing of hair or the painting of a portrait. That intimate embodiment, a moment of thirst in the sea of time—I aspire to more lines like this.

TQ: That line—“Thirst is a discipline of colour—of pain…”—is also one of my favorites in the book, and I’m glad it appears in the selection that TriQuarterly is privileged to share here. I interpret it as art and the creation of art is like an ouroboros—color requires thirst, which is a type of pain or want, and which, in turn, drives the yearning for color. An unending cycle of want and fulfillment-seeking. What does that line mean to you, and why are you drawn to it out of all the other great lines in the book?

JSS: I’m drawn first to the music—it’s wonderful in the body aloud. And—your ouroboros analogy is spot-on, perfectly mystical. Because, you know, if a line is good, the “meaning” can’t be translated. It’s metaphysical. Like the sonic, tactile embodiment of the brushes—its physicality is its meaning. Take rain’s chime with pain—it’s an easy rhyme, but I think it does some heavy work. The nursery rhyme simplicity holds the bank against more sophisticated slippage—like the tonal shift when the restrained declarative voice in the beginning of the sentence is overcome by longing…(again, with the brushes)…

I think of colour here as that which, like the Beloved, both can and cannot quench thirst. So, to say thirst is a discipline of colour, [AND] of pain—might imply thirst is a discipline of being caught between opposing forces. But the strangeness of color as an opposing force to pain is interesting to think about.

As is the word “discipline,” which could be interpreted as a punishment or an intentional practice. Or both. There’s brutality in that slippage. What does it mean when punishment of self is an intentional practice? What would it mean if it were not?

And I love that Thirst becomes the brushes’ sweep across the parched earth of the body. And then thirst becomes the rain. That’s some kind of magic. Like, what kind of rain is a drought? What kind of drought is the rain?

Of course, I’m not consciously thinking about this in the 15 second passage of line. I’m overcome by the music.

TQ: Erasure/blackout poetry has been around for many decades (and some argument can be made that the works of Sappho and other ancient textual fragments are a type of erasure, if not simply found poetry, as well). It seems, though, that interest in this poetic form has increased in the last several years. How do you see your book carrying on the discussion and tradition of erasure/blackout poetry? Were there any other works of erasure/blackout poetry or books of any sort (art, poetry, criticism, essays) that you feel really influenced Her Read?

JSS: Oh, golly. Well, I completed my MFA a year or so before I began Her Read and spent some time with erasures there: marvelous work of Mary Ruefle, Ronald Johnson’s Radi os, and Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter, which, as you mention, holds the fragmented remains of Sappho’s body of work as a work unto itself. Carson’s other work was also influential, including her essay “The Gender of Sound.” Time spent with haiku (especially Hass’s translations), Lorine Niedecker, and Dickinson helped me understand how much can be accomplished with a handful of words. This is especially helpful when working within erasure’s constraints! I also immersed myself in several book-length poems which—to borrow your phrase—might also be considered “song-like epics”: C.D. Wright’s One With Others, Deepstep Come Shining, and One Big Self, Alice Notley’s The Descent of Alette, Dante’s Inferno, and William Carlos Williams’s Paterson.

I read Elaine Scarry’s The Body in Pain recursively while working on Her Read—also Art Objects by Jeanette Winterson and numerous essays by Adrienne Rich, Toni Morrison, Mary Ruefle, and bell hooks. Andrew King’s essays on erasure in the Kenyon Review were super helpful. And Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, Valerie Martínez’s Each and Her, Solmaz Sharif’s Look, Harryette Mullen’s Sleeping with the Dictionary were all working on me while I worked on Her Read. I can also see how early engagement with E.E. Cummings, H.D., Diane Wakoski, T. S. Eliot, Robert Rauschenberg, Margaret Atwood, Martha Graham, and Judy Chicago impacted this work.

I came to Tom Phillips’s A Humument very late in the drafting of Her Read—and my visual work is absolutely not on par with Phillips, nevertheless when I finally read (a few versions of) A Humument, I was shocked at the numerous ways my female speakers seemed in conversation with Phillips’s male speaker. Both illumine moments of eroticism, dejection, fits, elation. And I borrowed some visual cues from A Humument in the final drafts of Her Read, as well.

I also read numerous erasures while working on Her Read—and continue to do so. I want to understand as much as I can about its lineage and progression. I hope my book carries on the tradition of using the poetic form of erasure to bear other erasures—the loss of cultures, individuals, human and otherwise—particularly the losses that occur when the authors of our world are the “conquerors.” I feel poetic erasure is most powerful when the new work is in dialogue with the source text, when dramatic tension is leveraged between one and the other. The result of that tension is a magical space for the reader to dwell—a liminal, listening space. Charged as the air between lovers or between the living who carry the dead. I hope my book creates such a space.