Rosellen Brown: Interview

Throughout her career, author Rosellen Brown has moved with ease among genres, from short stories to novels to poetry. Throughout each day, however, she’s traveled with equal grace between her top two priorities—writing and motherhood.

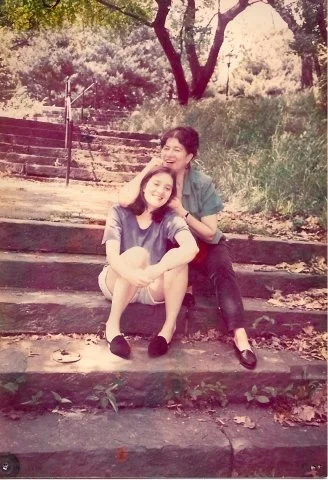

Many of her novels, such as Half a Heart, Tender Mercies, and Before and After, examine the intricate emotional roles of parents. She learned much about mothering firsthand, raising two daughters, Adina and Elana, with her husband, Marvin Hoffman. Currently, she teaches at the School of the Art Institute’s MFA in Writing program.

On a gray Sunday morning, Brown greeted me warmly as I arrived at her apartment, sitting high above Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood and filled with books and family mementos. As she took my coat, Brown asked if I would excuse her for a minute or two. She needed to finish a phone call with her daughter Adina, a nonfiction author now living in Israel, before we started our conversation.

After their I love yous and good-byes, she and I then talked about the often-conflicting demands of writing and mothering. Here is what she had to say.

I’m Rosellen Brown. I’m an author who lives in Chicago. I’ve lived here for fourteen years. I’m the author of ten books.

At the age of nine, I rather arrogantly stated—I think that would be the verb for it—that I wanted to be a writer when I grew up, not only because I like to write but because I thought it would combine well with marriage and motherhood. I’m very pleased that it worked out that way. I obviously did not have a clue that would possible, or whether I’d really want it when the time came, but clearly, this was something I had hoped for myself.

I’m the mother of two daughters. My younger daughter, who just turned forty, is Elana Hoffman, who’s a guidance counselor in New York City. And my older daughter, whose name is Adina Hoffman, is the author of two books.

I can’t imagine a life without writing. When I’m not doing it for a long time, I miss it. And when I read something wonderful, I want to do that.

Well, I worried when I had my first child that I might, you know, have trouble proceeding with my work. But I really didn’t have a lot of trouble. I never stopped writing. I had much more of a fear when my second child was born, that I wouldn’t have time, that I wouldn’t be able to split myself—you know, be able to manage both children. And kind of a funny and wonderful thing happened to me.

I was in the hospital, having just delivered my second baby in 1970, when my husband showed up—these were the days when you actually were allowed to stay in the hospital a full two days—my husband showed up with the galleys of my first story to be published. And that was the story that was going to be in TriQuarterly. And I remember that I pulled that thing across the bed that you have your meals on—you know, in the hospital—corrected the galleys, and thought, this must be an augury of the fact that, yes, I will be able to go on writing.

This was a story called “What Does the Falcon Owe.” It was a peculiar story made up of many parts. I got, when it was accepted, the most wonderful letter of acceptance I’d ever gotten from anyone, which was from Charles Newman, who was kind of a quirky editor there, who wrote essentially one line: “You must be beautiful,” which I have taken to heart and may be the only such assurance I had in my not-so-beautiful lifetime. But I thought, Oh, there’s a man who really did love this story.

TriQuarterly has been such a—such a marvelous discoverer of writers and perpetuator of good writing by people whose names had already been made.

I start every day by reading a little something. I’ve always done that in order to change the cadence of what I’ve been listening to, especially with children around. You know, you start the day saying, “Yes, there is a matching sock somewhere,” or, you know, “Hurry up, you’ll miss the school bus.” And then I always, of course, had to sit down and try to get into a very different place by reading something. But what that ends up doing to me within a few pages is [it] makes me terribly envious, jealous—makes me want to do it myself.

One of the parallels between motherhood [and writing] is you concentrate so hard on everything that you’re doing, every phase of your child’s life. And this is much like concentrating on every phase of your work.

I think the difference obviously is you can put your writing aside when you have to concentrate on your family. And you can’t put your children’s welfare aside.

The stars were in alignment somehow. I was intended to somehow, you know, if not master but at least deal with the intricacies of parenthood and writing. And there should be no reason for women to feel they cannot do all of this.

The first thing is be careful who you marry or with whom you have those children, because that is going to be a huge, huge—be a huge part of the capacity for you to do what you’re doing. The second thing is make it very clear to your children early that this is not a hobby, that this is something that matters to you. When you want to be alone and need to be alone, you do that.

There need to be times when the writing will slack off for lack of time, lack of attention, lack of capacity to concentrate on it. But your life is fortunately made up of many times.

I’m working on a few books right now. A couple of them are novels. One is in a drawer. It’s a novel that’s set in Chicago in 1893, actually, during the time of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Thing that I’m doing these days that gets the most response—especially from women of a certain age—is a book of stories to be called Late Loves.

I’m very proud of my daughters. They’re wonderful people, which is the most important thing to me. I mean, they’re smart and lovely, but what really matters is that they have a wonderful moral sense. They’re good people, committed to their work. They’re funny. They’re loving.

I’ve learned so much that was necessary for my writing from my having children. Now that they’re grown, I can’t imagine a life without them.

I cannot say enough about how happy and proud they’ve made me—made us. This was a joint effort. [laughing]

Read What Does the Falcon Owe?