Interview with Kristine Langley Mahler

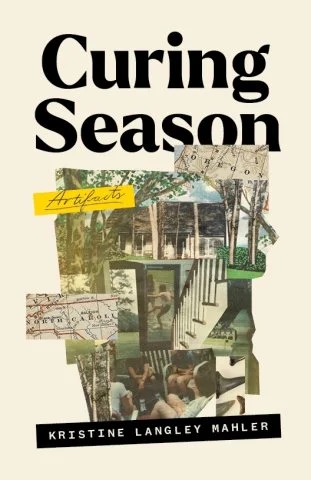

As the director and publisher of award-winning independent publisher Split/Lip Press—celebrating its tenth anniversary in 2024—Kristine Langley Mahler has overseen the fruition of many fiction, flash fiction, hybrid and nonfiction books. She’s also a talented writer, with her first collection, Curing Season: Artifacts, published in 2022, and another two books on the horizon. A classic coming-of-age memoir, Curing Season employs a variety of literary forms to revisit Mahler’s adolescence after her family moved to North Carolina. Home is a tenuous concept at any age, of course, and these linked essays explore the struggle of being a new transplant at a time when belonging is paramount and burgeoning identities are delicate, easily bruised, and still a mystery, perhaps to oneself most of all.

— Mandana Chaffa

Mandana Chaffa: Memories from the perspective of childhood, seen through the adult’s viewpoint require a subtle hand to balance it in a way that isn’t reportage, but also isn’t entirely in the hands of that child. How do you balance who’s steering the narrative? Has that changed appreciably in any of the essays from what you initially planned and what it ended up being?

Kristine Langley Mahler: I think there’s almost no way for me to avoid the endless recursion of a memory’s presence in both childhood and adulthood and so in my essays, I try to keep that behavior on the page. The adult Kristine holding the memory is only holding it because of the memory of the child Kristine; how can I fail to honor child-Kristine’s interpretation and yet how, with the responsibility of adult-Kristine, can I permit the original memory to stand inviolate? I would say I don’t balance who steers the narratives so much as I try to leave that toggling-between-the-two-selves on the page so the reader can see both versions (or at least the struggle).

MC: Each piece stands on its own, yet the accretion of them builds a special kind of narrative; technically speaking, how many ways did you consider arranging the book?

KLM: I was so certain of the original order! In early drafts of the book that would become Curing Season, I had done this really cool thing where the first essay (which didn’t even make it into the final book!) began with the line “I am going to have to start at the other end by telling you this: Annie is dead,” and then I ended the book with “Not Something That’s Gone,” where the final line is “Time is not a line but a dimension.” I was so proud of myself for turning the whole book into a Cat’s Eye: an elegy for Annie and also one massive homage to Margaret Atwood’s book. But I had kind friends who suggested that I would be missing the real narrative if I focused on friendship alone—obviously, a very important part of my experience in North Carolina, but only a facet of the real core, which was my desire to belong. I brought in a couple of pieces I had been working on—the wilder ones looking at history and belonging, “Out Line” and “A Fixed Plot” and “A Pit is Removed, A Hollow Remains”—and the book took on a new life. Once I understood what I was trying to say, the order became instantly clear and what you see now is what I knew I was trying to say.

MC: You now have your own kids; did revisiting these memories feel easier or harder as a mother?

KLM: My book about early adolescence came out as my children began theirs. I hadn’t noticed until someone pointed it out, but my family doesn’t feature very prominently in Curing Season and in particular, my parents are largely absent. Perhaps that’s a reflection on adolescence in general and the natural tearing-away that happens during those years, but I’ve thought more about how my parents’ absence from the book is a reflection on how desperately I tried to obscure so many of these emotions and events from my parents during those years because I felt ashamed. And my parents were nothing but supportive during my entire childhood (and beyond!)! So reconsidering these memories as a parent myself was less challenging than it might seem because I understand—and understood—that adolescence is navigated by the adolescent. My children are undergoing situations and emotions that I may not know—if I ever do find out—they encountered until much, much later. As a mother, I think I know what to watch for, but I also know the secretiveness inherent to adolescence.

MC: You know I can’t help asking this: but you’re a publisher of creative nonfiction, and I don’t mind saying, some terrific memoirists. How does that inform your own work? Similarly, as a workshop leader, does the teaching process alter your own work?

KLM: Oh my gosh, I am constantly inspired by my fellow memoirists and nonfiction experimenters, both those I’ve had the joy of working with in workshops and those I’ve had the honor of publishing through Split/Lip Press. I could name-check literally every nonfiction book we’ve got at SLP because I have learned from them all, but Calvin Walds’s nonfiction chapbook Flee, which won our 2020 Nonfiction/Hybrid Contest, still blows my mind. Reading experimentation by others always gets me excited to return to my own work and inspires me to try out different models.

MC: This collection is located in a certain place and time, of course, but I feel the energy of the other spaces you’ve lived and grown. How do they work their way into this collection? How do these childhood locations feel to you now?

KLM: I love this question because I’m a Cancer sun and my homes have always been essential to my sense of self. The homes I’ve had still pulse under my skin, a four-chambered heart with the four places I have gotten to hold as long-term homes (Oregon, where I was a child; North Carolina, where I was an adolescent; Indiana, where I was a teen; Nebraska, where I have been an adult). I’ve written more extensively about this in my book-in-progress, Home Trap, but the violent longing I held for my childhood home in Oregon, after we moved away from it, shaped the rest of my life.

MC: I know there are books in progress; can you tell us about them? What questions are you exploring? And have you ever written fiction? Is there a great American novel you’re contemplating?

KLM: A year is a slippery thing until it is ready to be shed, and my next book, A Calendar is a Snakeskin (forthcoming with Autofocus later this year) examines a year when all the snakes and bears and ghosts and ancestors came to my doorstep and demanded an accounting. The three connected essays of Snakeskin consider what it means to grow through selves and the fears that hover(ed) beside me as I slid toward the future. It’s got astrology and mothering and siblinging and homesickness and canyon pictographs and lots and lots of encounters with the other side and I am so excited to share Snakeskin because nothing’s been published from the manuscript before!

I am also working on a big book project called Home Trap about the privilege of home, ancestry, and what it means to belong to a place—which should come as no surprise to anyone who’s read Curing Season. And hell no, I have not written fiction: my life’s work is the truth, which fictionalizes itself enough!

MC: So much in flux in the publishing industry, not only since Split/Lip Press started, but since you’ve become Publisher and Director; what are the challenges and opportunities you see? And related to that, Split/Lip’s 10th anniversary isn’t too far away. Would you talk about what your thoughts were when you first took it on, and now, looking into the future?

KLM: You know, one of the precipitating events of Snakeskin was when the former director of SLP, Amanda Miska, contacted me in July 2019 and asked if I wanted to run the press. I’d been volunteering with SLP for about two years at that time and had been considering what I wanted to do with my career and when Amanda offered the director position to me, it was like an answer to an unvoiced dream. I go into this in much greater detail in Snakeskin (including all of the astrological significations around the timing), but it was a right-place-right-time-right-person situation. That being said, I had about a four month run-up to officially assuming the press, which included a website rebuild and rebrand, sunsetting the poetry books, incorporating the press as an LLC, assembling a core team, and getting all the financials in order—on top of the ongoing regular press operations I was helping with (book launches, book selections, submissions periods, preparing for AWP, social media, shipping book orders, etc). We relaunched on January 1, 2020 and let me tell you, no one can prepare you for how much time and labor it takes to run a small press with consistency, accuracy, and resourcefulness. In the last three years, we’ve added fourteen books to our catalog with four more slated to come out in 2023—significant when you consider that from 2014-2020, SLP had only published eighteen books total. SLP tends to function as a literary incubator, often publishing debuts by authors who go on to have considerable success with their subsequent books—Jared Yates Sexton, Kristen Arnett, Tyler Barton, Athena Dixon, and Tasha Coryell are just a few! We attract and spot early talent and so when we take on a book, it means that we believe wholeheartedly in the current work AND in the author’s future. Next year will be Split/Lip Press’s tenth anniversary and I look forward to continuing to position both our authors and their books for success all around.

MC: You wrote about being “eager to remember differently” and I think that one of the things I find difficult about memoir is that there is this Rashomon quality, as if we ourselves are the different perspectives. How I experienced a situation at five, the memory of it at twelve, the memory of it ten years later, and now, when my memory isn’t what it used to be: I can get lost in the inaccuracy of it all. How do you combat that to get words on a page and have it be real, without being entirely true?

KLM: I think that question is at the heart of an (unanswerable) question I often I ask myself while writing: how can all of these memories be true at the same time? I think of “truth” as the product of a series of coexisting filters through which I’ve put the same memories. The problem is that the 30-year-old self understands more of the nuances that led to X situation than the 12-year-old self who was experiencing and immediately processing it, but then the 22-year-old self was both more mature than the 12-year-old and yet closer to the original situation than the 30-year-old.

For instance, if your parents refused to let you do X when you were 12, you thought something very specific. At 22, reflecting on the situation, you probably thought something a bit different because you had more perspective. At 30, perhaps as a parent yourself, you likely considered their response differently as well. And yet at 40, you might turn it all on its head and revert to the same response you had at 12! All of those reflections are true and accurate understandings of the same situation, but which version is the closest to being “true”? The complications fascinate me! I suppose I try to leave that questioning on the page so that readers can see the ways that, at least for me, a memory is never finite.

MC: Can we talk about “Not Something That’s Gone”? It’s like a mini-novella of creative nonfiction, yet the pacing of it still feels like several shorter works that are woven together. Would you talk about how this piece was initially created, and how it moved through different versions before you first published it? There’s a real architecture at play here, and I’m aware how different rooms lead to others, and where there are rest areas and windows (to belabor a construct!).

KLM: “Not Something That’s Gone” is the piece I am closest to, the only one I’ll never read aloud at an event because every time I read it to myself, I cry. It’s the oldest piece in Curing Season and the one that underwent the most revisions. I began writing it as a senior in high school as a sort of response to Cat’s Eye by Margaret Atwood and, over the years, the meta-process that unfolds in the essay informed its final form—which I constructed around Cat’s Eye itself as I understood that my relationship with Annie was going to be a cat’s eye from which I would never leave. The narrative had to be controlled because the relationship was controlled; the relationship had to be shown as a twist inside a glass marble because the narrative would always be a twist inside a glass marble: contained, a re-cycling to the beginning, inconclusive. All loss is.

MC: And related to that: are essays ever truly done? Are major formative experiences ever done as fodder for a memoirist’s work?

KLM: As every writer says, an essay is only “done” when it’s published because it can’t be revised anymore! And as many memoirists have said before me, our major formative experiences are our lifelong fodder.

MC: I’ve really enjoyed your workshops. Do you have any craft advice you’d offer anyone hoping to start exploring memory-based work?

KLM: Thank you! I think one of the simplest inroads into writing memory-based work is to try writing into a photograph. Describe what is happening in the image and what you remember about the scene, and then begin to pull back from each description you’ve written to contextualize how and why. Then ask yourself, Why did I select this photograph? and follow the spiral because it will take you to the heart of your memory.