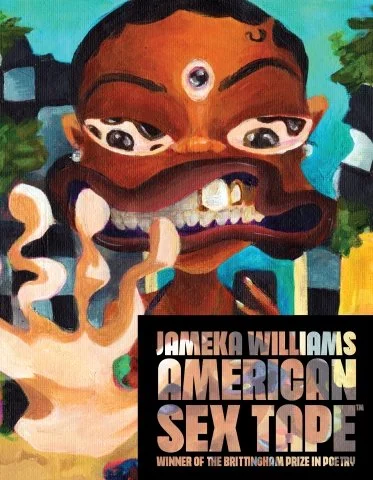

American Sex Tape™: Jameka Williams on Simulacrum, Scopophilia, and Scopophobia

Jameka Williams’s American Sex Tape™ is a triumph of a debut. Part cultural criticism, part self-investigation, Williams defies genre convention. Her poems burst onto the page with purpose, veracity, tenacity, and the self-assuredness of a long-established literary dynamo. I was humbled to parse questions from my own curiosity and unknowing, and I was grateful for Williams’s willingness to share her writing journey from high school English class with Mr. Walton to her pursuit of an MFA to this stunning debut. Williams needs little introduction: I’d like you, reader, to dive into Williams’s own words in this generous interview space she shared with me.

Laura Joyce-Hubbard: What has this process been like for you––writing and publishing your debut?

Jameka Williams: In hindsight, looking back at the very beginnings of this collection, I’m shocked that I wrote this book during some serious growing pains—the world, and the act of growing into Black womanhood, shook me, damaged me emotionally, physically, spiritually—while I was also trying to write a sound collection. That was hard to do. In 2016, I first began writing satirical persona poems from the perspective of a fictionalized version of socialite/media superstar/sex symbol Kim Kardashian. The book I imagined at the time was most concerned with a cohesive, thematically taut concept. This book I have now is messy and wily… in such a good way! That messiness, that wiliness, was born out of struggle: I moved to Chicago to enroll in Northwestern’s MFA in Poetry and Prose. I was broke all the time, deeply lonely and isolated. I was getting physically and mentally sicker. I had suffered sexual violation in 2019. My small world was growing bigger here in Chicago, and not always in the best way. My world has been rocked by so many tests and so many tragedies these past five years.

All my aesthetic and artistic concerns about the original concept for this collection went out the window. I’m no longer the same twenty-five-year-old woman writing this, who felt very confident in her ability to comprehend and critique the world and craft poetry from it. My writing, my reading, my study of poetry had to evolve, not only to write this strange, brave little book—but simply to survive adulthood in my late twenties. I’m thirty now. American Sex Tape™ is being published six years after the first poem in the book was published by Gigantic Sequins. I feel vindicated in a way. This book that has gotten weirder and funnier and sadder and sexier as I’ve gotten weirder and funnier and sadder (and hopefully) sexier is now in print and in the hands of an enthusiastic audience. It’s as if all of the growing pains were worth it.

LJH: Six years—congrats! American Sex Tape™ is such a compelling title. It’s clear that the title is meant to evoke sex and the commodification of sex. I’m wondering if you can speak on the use of the trademark symbol in the title?

JW: I know that I’m going to do a poor job of relaying the story of how the trademark came along. I honestly do not remember clearly. But I owe the title—trademark and all—to Simone Muench, who was one of my craft professors and thesis advisors at Northwestern. I had some truly uninspired titles for this book. Simone’s brilliance is that she understands the shape of my dark humor and my cheekiness, often before I even understand the point (the joke) I’m trying to make. For me, and I suspect as well for Simone, American Sex Tape™ indeed speaks to the triumvirate of American popular culture: sex, money, and our addiction to looking/being seen. But the trademark feels like an inside joke between Simone, myself, and the revising process. Not only because Simone’s title is genius and we didn’t want it getting “leaked” (much like Kim K’s sex tape) or being stolen if I spilled the beans on social media about what the title of my book is. The trademark symbol at the end all has this kind of “Fuck You, Pay Me” attitude! Like All the blood, sweat, and tears that went into revising this energetic, feral book—I’m identifying the source of this artwork, which is me, by slapping an almost comically meaningless trademark on it.

LJH: Can you talk about your relationship to the spectacle that is the Kardashian family and how it informed your book of poetry?

JW: My only relationship to the Kardashians, specifically Kim, is that I am a passive viewer interested in attempting to not only understand them as a media commodity but why that seems to affect my self-image so much. I’m not a superfan, but I do find them amusing. Kourtney’s my favorite. But early on in the life of the book, I remained fascinated and frustrated by their triteness and their consequence in pop culture. They raised so many questions for me in my mid-twenties, coming into an understanding of my value as it pertains to existential questions of worth, and my cultural and political value in this country, as a Black woman. How come the Kardashians’ wealth protects them? Are they truly emancipated sexually if they sell sex? Why use your body and manufacture your presence in the world for profit? Why do they have such a disdain for Black influence on the very culture they repackage and sell to us? Why are they so bored with their power over our culture? Why do they want to be immortal so badly? The questions go on and on. There’s a lot of spectacle in American Sex Tape™, and they are an endless source of spectacle to tap.

LJH: In your gorgeous opening poem, “American Sex Cento,” you use seventeen sources as varied as Walt Whitman, Lucille Clifton, William Shakespeare, and Maya Angelo. Can you talk about your inspiration for this poem—how you choose the specific sources and lines?

JW: Thank you! It is my favorite poem in the collection. It very much is the “thesis statement” of the project. The inspiration for “American Sex Cento” begins with confessing that I’m a lousy student. I struggle often to write within the constraints of closed form. Many poets, and rightfully so, see how closed form presents freedom when you understand the mechanics of what you intend to convey inside of form. I simply struggle with meter and line breaks, counting syllables etc., etc. I spent a lot of time working on poems for this collection with the hope that I could meld free verse with my own inventions to avoid closed form all together.

But ultimately, I felt compelled by several mentors, including Simone, to attempt a closed form. I have always loved the cento form because it is incredibly open to possibilities. And I don’t have to count meter! Popular culture, so central to my artistic obsessions, is shaped by curation. A cento is, after all, curated. A cento is a museum—and like the art within these institutions, a cento permits poetic lines to be pilfered, re-presented. and re-dressed to lock the viewer (the reader) into a room with double meanings. The first is the newly formed thesis from the curation of placing these disparate “stray” lines of poems in conversation with one another. And the second meaning is what these lines meant within their original poems. I set out to lift lines from poems about America or Americanness (Whitman and Langston Hughes, for example) and to marry them with lines lifted from love poems, or at least sexually charged poems (e.g., Clifton and Addonizio). The poem came together quickly: often our literary heroes described their relationship to Americanness like that of a tumultuous affair—ecstatic like a religious experience and/or plagued by brutality and exploitation like American history itself. And certainly, this affair with our nation will always remain a vain exercise in patriotism and individuality.

LJH: I love the marriage of Americanness with love poems and sex as a constraint you gave yourself. Is there anything else you would like the reader to understand or anticipate as they begin to read the collection with this marvelous cento?

JW: I love that the cento opens the book; I wanted to set the pages ablaze before we even start! Not only do I want the cento to make clear what my investigations will be in this collection, I also want to set the tone with “American Sex Cento.” There’s a lot of bravado and fierceness in this poem. This poem is a fiery address from the underdog to his overlord, from the enslaved to their master, from the abused to her abuser. This poem tells the reader this book is an angry, witty retort to everything we believe about American self-righteousness and American culture. My only regret is that not all of the poets present in “American Sex Cento” are American (I’m sorry I cheated! Once again, I’m really really bad at following the rules of form and my own created, arbitrary rules).

LJH: It’s wonderful when messing with formal constraints is as productive or more than following them. I’m curious about the two sections, “Scopophilia” and “Scopophobia,” that mark the two distinct movements in the book. How did you come to the decision of forming the collection into these two sections—the love of seeing and the fear of being seen?

JW: A major motif in American Sex Tape™ is the act of looking. The camera’s eye, and the relationship between viewer and looked-at subject present themselves in nearly every poem. We are a cultural collective addicted to viewing. We are voyeurs, attempting to deduce meaning and shape an identity of self and Other through the act of looking. This fascinates me. It’s a dangerous pastime. I am addicted to viewing, hooked to my screen. We’re always scrolling, trying to get that hit of video-heroin until all those pixels become a meaningless jumble of incels rambling and cats doing backflips and stolen cultural dance moves and Karens.

There’s a “can’t-looked-awayness” about American popular media, thus why it was easy to begin this collection with the most looked-at person in the world, Kim Kardashian. But while Kim Kardashian is both fun and problematic, I am also interested in our viewing being of greater consequence. The American pastime is watching the news: playing passive witness to how American history unfolds with every political betrayal, with every shameless cash grab, with every car crash or mass shooting. We value witnessing, and yet, our witnessing is often in service of objectification and subjugation.

It was important for me to divide this book in two, and to insist that the scopophilia (I believe first coined by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey), the love—erotic and addictive—of objectifying via sight is often proceeded by the horror of understanding your power as a viewer, or the fear that being viewed will lead to your imprisonment. The power dynamic between viewer and subject has always been sick with the history of exploited Others: women, Black/brown/Indigenous peoples, the poor, and the Others who do not fit into the American experiment. I’m often writing myself in the position of power, holding the camera at subject and making my point of view the one that determines fate. But, within American Sex Tape™, I turn the camera. I point it outwards, and then I point it at myself. It’s pleasurable and powerful, and yet it also reveals my vulnerabilities and my uncertainties.

LJH: Speaking of turning the camera at yourself, how did you strike a balance between cultural criticism and self-reflection in this collection?

JW: I’m not confident that I successfully struck a balance between cultural criticism. I certainly hope that I did. I say this because I was nearly finished with the book in my final year at Northwestern when the instruction of Ed Roberson, Megan Stielstra, Simone Muench and Faisal Mohyuddin finally sunk in, and I came to my senses: there was too much Kim Kardashian and not enough of me. It’s funny! I was holding onto this position that my book had to be entirely cultural criticism because that was the so-called “reason” I had even begun this collection. There should be no “I” or “me” on the page because I’m not the subject of my ire! Why else spend money on Kim Kardashian’s book of selfies?

It was an absolutely fair observation my professors shared that I needed to find a strategy to not only satirize but humanize Kim Kardashian, but also I, the working-class Black woman poet, is more interesting than Kim Kardashian. I had to edit a lot of Kim out in the long run to write a braver book. I believe I simply wasn’t ready to write into the muck of introspection and self-reflection, murky and embarrassing and spiritually fraught, until very late in the program. Kim Kardashian is ultimately a kind of boring person—her wealth is boring and her controversies are boring. It no longer was important to me to write about her, it became almost essential, for the sake of just getting to understand myself better, to turn the camera on myself—not only about how I feel about Kim Kardashian, excess wealth, trivial pop culture, sexuality, and feminist discourse, but also how those things have shaped my personal background and my everyday life. So much of this book reads to me like a diary more than cultural criticism!

LJH: I love that self-revelation in the midst of generating your collection. Can you talk about how sexuality functions in this book?

JW: At a pre-publication celebration for this book in Madison, WI, on the campus of University of Wisconsin-Madison, this question was posed to me by a creative writing student in attendance in a similar fashion. But their concern was with the negative depictions of sex/sexuality present in American Sex Tape™. They asked if I was successful at combating all the challenges of sex in our culture, especially in the wake of “Me Too” and its reckoning. I’ll repeat here what I shared there: I don’t think I’ve rescued sex from patriarchal exploitation or racism or classist assertions. American Sex Tape™ maintains a deeply cynical and horrified vision of our sexual culture almost to the end.

Some days, I feel bad about my negativity. The book concludes in “Since I Laid My Burden Down” with an almost “meh” resolve concerning sex and sexuality: the “I” is by herself in rote masturbation; she is “not too cold or too hot.” But this is the most whole and most content and the most sexually safe she has felt in a very long time. There are very few positive visions of sexuality in the book: I cite the only love poem in the collection as a fair example, “Black, or the Natural World Doesn’t Know Me,” which I wrote about my boyfriend and I sharing long walks through Winnemac Park during quarantine. In many ways, sexuality, as it is presented here in the book, does not function. There is dysfunction because of predatory practices among genders, because of racial fetishization, and/or because the capitalistic commodification of our erotic selves.

I wish that I had rescued sex from the clutches of our collective lack of tenderness and charity and respect toward one another and the life-affirming practice of bodily autonomy. For me, bearing witness to the shit and struggle comes before I can fantasize a better (sexual) world for us all. I will offer this: I think once sex and sexuality are divorced from capitalism and commodification, meaning when sex is no longer “sexy,” catering to the exploitive and prejudiced desires of the historical oppressors, than sex will function. Sex will be joyful and no longer transactional, and it will be spiritual and will have the power to shape ourselves and our partners. But it will absolutely look so, so, so boring to capitalists. That’s my deepest hope.

LJH: Thank you so much for that profound and honest response. It’s such a complicated topic, and I’m grateful for your thoughts. Speaking of hope, what do you hope American Sex Tape™ adds to current discourse on race and gender?

JW: I believe American Sex Tape™ speaks most clearly to this as it concerns much of our public discourse on race and gender: race and gender are performances, and we will become more generous and just as a society when we stop acting. When we leave the stage. When we smash our mirrors and turn into the sun. When we tell off the cameraman and tell him to stop making spectacles of us.

Kim Kardashian is the ultimate performer: she performs sex and gender as a supposed emancipated body (emancipated from capitalism? I don’t think so, but possibly emancipated from sexual repression, in her own words). She performs race through her ethnic ambiguity and her shameless cultural appropriation. She performs money and excess. Americans are the ultimate performers, too. Our history reveals this to us. We perform politics and we perform patriotism. We perform self-righteousness. We perform for the Haves, and we often ask the Have-nots and our marginalized communities to perform invisibility or bondage. But our public and private performances of selfhood are shaped by the arbitrary and historically inhuman practices of racial capitalism and white supremacist patriarchy.

I believe American Sex Tape™ asks: Why perform? It says: Look at how our performances for these historically violent and trite institutions have created a false sense of inferiority in us. I’m directly speaking to young people like myself who have come from little financially or have been mistreated because of their race or sexuality or gender expression. This daily performance of the right and wrong ways of being Black or brown or woman or gay or disabled or poor only serves the capitalist project, and we suffer the consequences culturally: self-hatred or self-denial, miscommunication or alienation, and broken kinships or communities.

LJH: Thank you for saying so. The personal cost of performance is so high. I already know I’ll be re-reading your answers as I re-read your poems, as so many of them convey this idea. My next question stems from a personal curiosity, which will hopefully be relevant to readers, too. I appreciate that a poetry collection relies on a cumulative effect, with one poem leading like a stair into the next. That said, if you could only read one poem in this collection to encapsulate your project, what poem would it be and why?

JW: There are a number of poems that I find encapsulate this project: “American Sex Cento,” “Nothing Is Promised,” “The new american girl doll is no longer a slave.” But I want to make an argument for “Since I Laid My Burden Down.” It is the denouement that I wanted for this book, and the poem I feel most spiritually satisfied with. I wrote the poem as an attempt to bring myself into light, as depression and anxiety were periodically making it difficult for me to sleep, eat, go about the day-to-day grind of work and school, and make art. So many family, friends, and mentors were holding me in their hearts and into the light with my little successes here and there, that writing “Since I Laid My Burden Down” felt like I owed a poem of gratitude. The poem has mood swings! It opens triumphantly with Beyonce. It closes with some self-deprecation. But in the middle of this poem, there’s a steely resolve to not be a victim again, when so much of American Sex Tape™ focuses on how our culture victimizes the smallest of us. In this poem, there is an admission to put the sword down for a second, warrior: “you will not be buried twice [...] I don’t set names to anyone or anything anymore / I just roll back into the sea.” But I believe this poem also takes stock of how we’ve survived all that’s come before.

LJH: I’m so glad you made a case for “Since I Laid My Burden Down,” as I loved that poem. It is a reminder to take stock: I see and feel that. Can I ask you about the formal decision you make in the book? It has such a formal variety, which complements the amount of ground you cover. I’m wondering what your process is when deciding a poem’s form. Is it intuitive? Is it something you consider before or as you’re writing, or not until afterwards?

JW: It’s an intuitive process for me. I’m often performing or singing threads of ideas or imagistic phrases in my head and then throwing the mess together on the digital page. I just need to throw a bunch of shit at the wall and see what sticks –– what still feels fresh to me or feels energetic and needed to write the poem. Form and shape come to me later in the revising stage, when I try to fit all these pieces of rhetoric, dreams, snippets of speech, diary entries, pop culture allusions, tweets, etc., into something cohesive.

LJH: You do a great job lassoing that “messiness” and “wiliness” you mentioned before, striking an admirable balance between wildness and constraint. Shifting gears a little, but I love the acknowledgement you include in the book to one of your first creative writing teachers from high school. Can you talk about your influences and how you see them appearing in your work?

JW: Funny enough, my favorite English teacher from high school, Mr. Walton, does not appear in any obvious way in this book. He didn’t inspire any particular poem. I don’t quote him in any lines. He simply is an inspiration because I deeply valued his instruction then as a teenager, and still now, as an adult, his patiences and style of teaching remains dear to me. I went to a conservative, private, Christian high school—small and insular. Mr. Walton would not approve of this book! This book is worldly and profane and brutish at times. Not lady-like or godly. I felt compelled to acknowledge Mr. Walton because the selection of literature he taught always moved me toward further investigation of my beliefs. And he would recite poems so beautifully! His selection of literature always moved me. The way he performed was energetic and textured. That has always stuck with me. His recitation often comes to mind when I’m crafting poems in my head in the early stages, as well as when I’m performing my poetry in front of an audience.

LJH: Would you like to share with readers what you are working on now?

JW: I am working on work–life balance! I am working on trying to remember to text my friends and call my mom and be kind and laugh at myself more. I’m really working on myself now that the storm clouds have receded. I’m not really into all the “self-care” discourse and toxic positivity stuff online. Self-care is a psy-op for real! But I will say I’m working on remaining interested in becoming a better communicator and curator of ideas and thoughts. But I’m not taking those ideas to the public just yet. Just my sweetheart, and my sister, my friends, and my parents. This is all a cop-out! All that to say that I’ve been obsessed with Édouard Manet’s Olympia and Olympia’s Black maid. I worked on an essay while at Northwestern. So I don’t suspect Olympia’s maid will find her way into my poetry, but something longform.

LJH: What advice would you give other poets working on their first collection?

JW: Write with abandon first! Editing yourself—and I don’t mean revising poems, I mean stopping yourself from experimenting because you’re convinced you or the other poets have a set routine on how to get to the heart of their work—doesn’t make for a great writing experience. The first book is rough and ragged and messy. Sit with the mess for a bit. Write with making a mess in mind. It’s more fun that way.

Jameka William’ American Sex Tape™ is available wherever you buy books. Indiebound here.