Steven Johnson and the modern day commonplace book

Steven Johnson, author of The Ghost Map, has posted the transcript of a fascinating lecture about the practice of "commonplacing" and the implications of new reading technology on sharing and remixing digital text. During the Enlightenment, scholars and thinkers usually kept a "commonplace book," or research scrapbook where they transcribed interesting passages of things they read, augmented with their own notes.

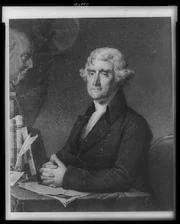

You can see the obvious parallels to modern media. These commonplace books were the original blogs, tracing the development of minds like Jefferson, Milton, Bacon, and Locke. Of course, they didn't have the benefit of copy-and-paste, so everything was written and rewritten by hand. The internet, e-books, and digital text combined with programs like Evernote, Yojimbo, and your favorite blogging platform allow us to assemble public, shareable commonplace books that would curl their powdered wigs.

But Johnson points to a disturbing trend toward locking up this text to prevent easy remixing, particularly on the iPad and Kindle where it is difficult if not impossible to cut, paste, and share passages of text:

... we have two potential futures ahead of us, where digital text is concerned, or that the future is going to involve a battle between two contradictory impulses. We can try to put a protective layer of glass of the words, or we can embrace the idea that we are all better off when words are allowed to network with each other. What’s the point of going to all this trouble to build machines capable of displaying digital text if we can’t exploit the basic interactivity of that text?

I think the implications of this trend are more severe for academic writing and journalism. To the extent that creative writers reuse text, they internalize their reading and learn to mimic or pay homage to the styles of influential authors rather than reproduce entire passages themselves. Wholesale re-appropriation is generally frowned upon (see the recent dustup over German teen author Helene Hegemann). That's not to say being able to cut and paste bits of text at will isn't useful for study and researching a novel, it's just not as crucial to the final product as it is for a scholarly monograph.

I certainly sympathize with writers like Johnson, Cory Doctorow, and others who are sensitive to the issues of copyright and content restriction, but at the same time their arguments are often of the slippery slope variety, i.e. what could happen if every piece of text was locked under that layer of glass. I simply don't believe the technology will allow it. Johnson points specifically to the limitations of the New York Times app on the iPad, but the main Times website, which you can share to your heart's content, works perfectly fine in the iPad's web browser, so well in fact that it's the go-to demo for their ad campaign. There also isn't a piece of copyright protection software that either hasn't been cracked by some enterprising hacker or abandoned by the vendor because of the burdens it places on users. That's why you now see Apple selling unrestricted MP3 files to compete with Amazon.

And of course, nothing could prevent a burgeoning scholar from copying passages of text by hand, just as the great thinkers of the past did. From my experience, that's the best way to remember things anyway. But like Johnson, I just hope it doesn't come to that.